RESEARCH ARTICLE

A Simple Method to Reduce Interpretation Error of Ages Estimated from Otoliths

Bradley J. Smith1, 3, Daniel J. Dembkowski1, 4, *, Daniel A. James2, Melissa R. Wuellner1

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2016Volume: 9

First Page: 1

Last Page: 7

Publisher Id: TOFISHSJ-9-1

DOI: 10.2174/1874401X01609010001

Article History:

Received Date: 30/4/2015Revision Received Date: 30/11/2015

Acceptance Date: 1/12/2015

Electronic publication date: 25/3/2016

Collection year: 2016

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

Abstract

We designed and tested a novel otolith viewing apparatus termed the otolith illumination device (OID) to ascertain if its use would result in a reduction of interpretation error as determined by increased precision of age estimates obtained from otoliths of walleye Sander vitreus and smallmouth bass Micropterus dolomieu. Clarity of annuli on otolith sections viewed with the OID was generally greater than clarity of annuli on sections viewed with an alternative method. OID-based age estimates were equally as, and in some instance more precise than ages estimated using the alternative method. Additionally, no systematic differences in coefficients of variation across ages were detected between the OID and alternative methods of fish age estimation. Results suggest that the OID may be useful for inexperienced readers and is a viable option for reducing interpretation error, which may improve reader efficiency and accuracy and precision in estimating fish ages.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate and precise age estimates are critical for the effective management and understanding of fisheries resources because dynamic rates of recruitment, growth and mortality depend on these data [1-3]. Techniques related to preparation of calcified structures (e.g., sectioning, polishing, and cracking and burning) [4, 5], as well as methods for enhancing contrast and visibility of annuli during the age estimation process (e.g., submersing otoliths in immersion oil and use of microscope light filters) have led to improvements in accuracy and precision of age estimates [6, 7]. Despite these improvements, process error (i.e., error related to a technique) and interpretation error (i.e., individual subjectivity) still lead to reductions in accuracy and precision in age estimation [3, 8].

Reductions of process error are crucial for providing accurate and precise age estimates determined by a reader [3]. Although multiple structures such as scales, spines, otoliths, cleithra, and fin rays can be used to estimate age [9-11], the use of otoliths is considered to yield the most precise age estimates for a broad range of species [e.g., 12, 13] and sizes [e.g., 13, 14], there by representing a substantial reduction in process error.

Although process error has largely been reduced by the use of whole or sectioned otoliths, reliable age estimates are none the less dependent on the ability of a reader to identify and enumerate annuli. Improvement of methods to facilitate the identification of and ability to enumerate annuli (i.e., interpretation) would further increase accuracy and precision of fish age estimation. We designed and tested a novel otolith viewing apparatus termed the otolith illumination device (OID) to ascertain if its use would result in a reduction of interpretation error as determined by increased precision of within and between reader age estimates.

METHODS

Sagittal otoliths were removed from walleye Sander vitreus and smallmouth bass Micropterus dolomieu sampled using gill nets in Lake Sharpe, South Dakota (a main stem Missouri River reservoir) during 2006 and 2007. Upon removal, otoliths were wiped clean and placed in individually labeled vials. Otoliths were mounted convex side down in a plastic mold (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and embedded in epoxy (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL; Epoxicure resin and hardener) to form a block for sectioning. Otoliths were sectioned into 0.2-mm thick sections encompassing the focus using a low-speed saw (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL; IsoMet Model 11-1180). Sections were briefly examined under a dissecting microscope following each cut. If the first section did not include the focus, a second section was taken and the first was discarded. Each section was lightly polished using wetted 1,200-grit silicon carbide sandpaper and placed into labeled vials.

Before examination by two readers, otoliths were randomized following the methods of [15]. Sample vials were drawn at random from a bin and numbered sequentially with black ink. The samples were then re-randomized and numbered sequentially with red ink. To ensure independent readings and minimize potential reader bias, otolith sections were read first in order of the black numbers, then again in order of the red numbers. Both readers were relatively inexperienced in estimating ages from otoliths but had experience estimating ages from scales. Inexperienced readers were selected because we expected improvements in precision resulting from use of the reflective dish to be most apparent for unseasoned readers.

The OID consisted of two concentric glass petri dishes, with the open side oriented upward (Fig. 1). The smaller diameter dish was seated (i.e., caulked) at the top of and within the larger dish. A small gap of empty space between the bottom of the smaller dish and the bottom of the larger dish was present (Fig. 1). The entire exterior surface of the OID (i.e., the outside of the bottom and sides of the larger petri dish) was painted with non-reflective black spray paint. A layer of immersion oil thick enough to cover otolith sections was placed in the reservoir within the smaller (i.e., top) petri dish. Otolith sections were submersed in the immersion oil and an external light source was used to direct light downward into the OID. Light is passed through the immersion oil into the empty space of the OID below the otolith section, reflected upward, and then refracted within the immersion oil, thereby illuminating the otolith section from every angle. The intensity and position of the light source were manipulated to obtain the highest clarity image possible.

|

Fig. (1). Schematic of the otolith illumination device used to estimate ages from walleye and smallmouth bass otoliths. |

The alternative method included viewing an otolith section on a dark background with incident light supplied by an external light source. A drop of immersion oil was placed on the sections to increase the contrast between translucent and opaque bands (i.e., annuli) and the intensity and position of the incident light source were manipulated to obtain the highest-clarity image possible. Although numerous options are available for preparing and viewing otoliths [see 7], the alternative method evaluated in this study has been used successfully for multiple species in multiple localities [e.g., 15, 16-21] and is particularly useful for age estimation from large otoliths (i.e., older fish) [7].

Each otolith was read twice using the OID and twice using the alternative method by each reader with a binocular dissecting microscope at 4 - 10X magnification depending on otolith size. The binocular dissecting microscope was fitted with an Olympus OP2-BSW camera and otolith images were projected onto a larger screen using an Olympus visual imaging software package (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA). Consensus ages were agreed upon following independent age estimation for otoliths with estimated age discrepancies between readers.

Within and between reader precision was evaluated by comparing coefficients of variation (CV) from ages estimated using the alternative method and the OID for each species. Because the age estimates were not independent of one another, a paired t-test was used to test for differences in CV. A mean difference in the CV between the alternative method and the OID greater than 0 would suggest a reduction in variability and thus an increase in precision in age estimates. A generalized linear model (GLM) was used to test for age-dependent trends in mean CV between age estimation methods. Specific attention was given to potential differences between age estimation methods for older walleye and smallmouth bass. Because known-age fish were not available for this study, consensus ages were assumed to represent true fish age [sensu 22]. Analyses were performed with walleye and smallmouth bass samples from both years combined. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.10 to reduce the probability of making a type II error (failing to detect a difference in CV or systematic trends in CV across fish age) and all analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System software package [23].

Mean (SE) coefficients of variation for ages estimated from smallmouth bass and walleye otoliths using a novel otolith illumination device and an alternative method. Analyses were stratified by species and reader. Results were considered significant if P < 0.10.

| Otolith illumination device | Alternative method | t-statistic | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smallmouth bass | |||||

| Reader 1 | 8.79 (1.64) | 8.19 (1.42) | 0.17 | 92 | 0.86 |

| Reader 2 | 10.87 (1.18) | 12.05 (1.74) | -0.17 | 91 | 0.86 |

| Between | 18.94 (1.32) | 18.53 (1.98) | 0.21 | 96 | 0.83 |

| Walleye | |||||

| Reader 1 | 12.22 (1.64) | 16.88 (1.81) | -2.41 | 92 | 0.02 |

| Reader 2 | 16.24 (1.71) | 16.27 (2.05) | 0.13 | 93 | 0.89 |

| Between | 22.86 (1.52) | 25.48 (1.95) | -1.87 | 96 | 0.06 |

RESULTS

Ages were estimated for 99 walleye and 98 smallmouth bass (total age estimates = 788). Total length ranged from 123 mm to 760 mm for walleye and from 126 mm to 491 mm for smallmouth bass. Opaque and translucent bands were visible on all otolith sections and consensus ages ranged from 2 to 10 for walleye and 2 to 8 for smallmouth bass. Although most smallmouth bass were ages 2-6 and most walleye were ages 2-7, fish of all ages were included in the analysis to encompass variability in precision related to fish age.

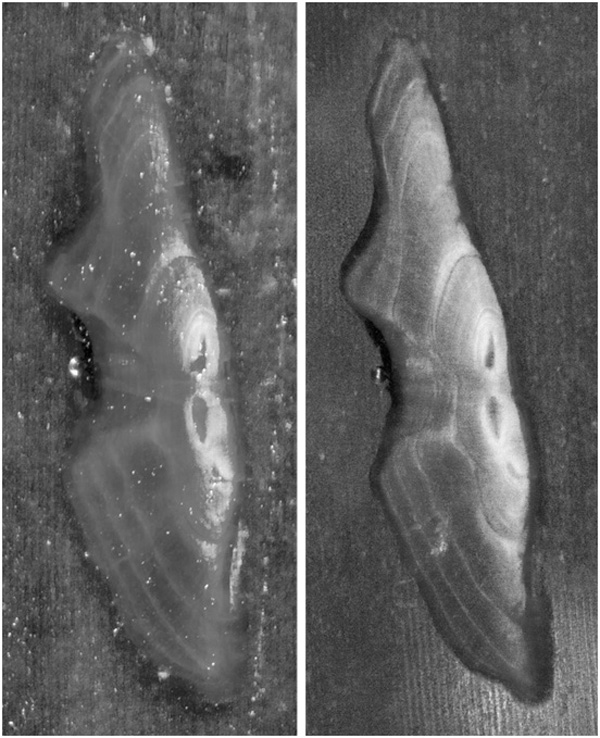

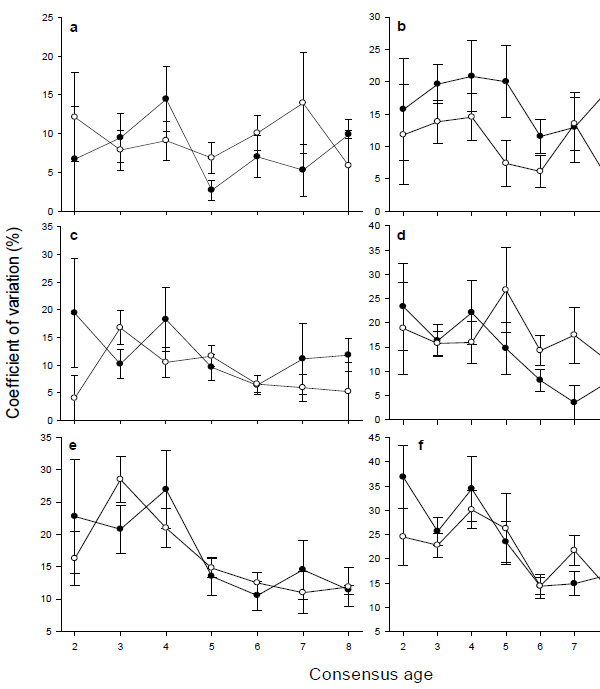

Clarity of annuli on otolith sections viewed with the OID was generally greater than clarity of annuli on sections viewed with the alternative method (Fig. 2). The increased clarity was reflected in estimates of within- and between-reader CV, wherein OID-based age estimates for walleye and smallmouth bass were equally as, and in some instance more precise than ages estimated using the alternative method (Table 1; Fig. 3). Additionally, no systematic differences in CV across ages were detected between the OID and alternative methods of fish age estimation (Fig. 3; all GLM P > 0.10). For reader 2, precision of ages estimated using the OID was qualitatively greater than that with the alternative method for age 7-8 smallmouth bass and age 9-10 walleye (Figs. 3c, d). Similarly, between reader precision of ages estimated using the OID was qualitatively greater than those with the alternative method for age 8-10 walleye (Fig. 3f). Conversely, for reader 1, precision of ages estimated using the alternative method was qualitatively greater than those using the OID for age 9-10 walleye.

DISCUSSION

Age estimates using the OID were equally as, and in some instances more precise than ages estimated using the alternative method frequently used by biologists and researchers. Although many options exist for preparing and reading fish otoliths [e.g., 4-7], results herein suggest that the OID has value in reducing interpretation error and may constitute an additional tool for improving precision of age estimates, particularly for readers with little or no experience.

We used readers with relatively little experience in estimating ages from otoliths. Management agencies sometimes rely on ages estimated by inexperienced readers [24]. Often, technicians, seasonal employees, young researchers, and students have little experience with fish age estimation and sometimes receive little training before collecting “real” data. Experience level does affect precision. For example, a study examining the accuracy and precision of crappie (black crappie Pomoxis nigromaculatus and white crappie Pomoxis annularis combined) ages revealed that precision was less for inexperienced readers than for experienced readers [25]. In another study, readers with more experience displayed greater accuracy in estimating ages from daily otolith rings than less experienced readers but inexperienced readers who polished their otoliths obtained more accurate ages than inexperienced readers who did not [26], implying that inexperienced readers can improve precision when aided. Because reader experience level influences accuracy and precision of age estimates, any improvement in ability to increase precision will provide more reliable data. In some instances, our inexperienced readers showed improvement in precision by using the OID, which further suggests that its use was beneficial and demonstrates its possible utility as a teaching device for use in agency or academic settings.

In addition to benefitting inexperienced readers, the OID may improve accuracy and/or precision for older fish and very young fish. For example, for smallmouth bass older than age-6 and walleye older than age-7, use of the OID generally resulted in qualitative improvements in precision of age estimates compared to precision of ages estimated using the alternative method (but see Fig. 3a, b), suggesting that the OID may be particularly valuable in estimating ages for older or long lived fishes with many annuli. Age estimates from older fish are typically less precise and accurate than age estimates from younger conspecifics due to the slowing of somatic growth and resulting compression of annuli [8, 11]. We also posit that the OID may be useful in studies focusing on population dynamics during early ontogeny when enumeration of daily otolith circuli may be necessary. In these instances, even minor improvements in precision would be beneficial, but further research is needed to validate these claims. We also recommend continued research to examine the value of the OID when used with different species, aging structures (e.g., whole otoliths, cleithra, and fin spines or rays), and readers with varying levels of experience.

In conclusion, the OID is a simple, inexpensive apparatus, readily and easily constructed with common laboratory equipment that aids in improving precision of age estimates, particularly for readers with little experience. Even if the OID did not improve precision in all instances, it remains an option for improving precision and accuracy (Fig. 3) and making structures easier and faster to age, which could lead to improvements in efficiency (i.e., labor savings) for fisheries managers and researchers.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this project was provided by Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration funds (Project F-15-R, Study 1518; administered by the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks) and by South Dakota State University. We thank B. Bethke, J. Dagel, B. Graff, and J. Grote for laboratory and field assistance, M. Wagner for assistance with digital imagery, and M. Brown, N. Scheibel, and D. Willis for providing helpful reviews of earlier drafts of the manuscript.