REVIEW ARTICLE

Landlocked Fall Chinook Salmon Maternal Liver and Egg Thiamine Levels in Relation to Reproductive Characteristics

Andrew Doyle1, Michael E. Barnes2, *, Jeremy L. Kientz2, Micheal H. Zehfus3

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2017Volume: 10

First Page: 23

Last Page: 32

Publisher Id: TOFISHSJ-10-23

DOI: 10.2174/1874401X01710010023

Article History:

Received Date: 11/11/2016Revision Received Date: 04/01/2017

Acceptance Date: 23/01/2017

Electronic publication date: 30/06/2017

Collection year: 2017

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Object:

Landlocked fall Chinook Salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha in Lake Oahe, South Dakota, typically experience poor reproductive success.

Introduction:

Salmon diets consist of rainbow smelt Osmerus mordax and other potentially thiaminase-containing fish that could impact reproduction.

Methods:

The thiamine levels of spawning female Salmon, eggs, and reproductive characteristics, were measured in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2005.

Results:

Thiamine concentrations varied significantly from year-to-year, with the highest mean values recorded in 2001 at 8.70 nmol/g in maternal livers and 28.80 nmol/g in eggs. Most of the thiamine in the eggs was present as free thiamine, while most of the thiamine in maternal livers was present as thiamine pyrophosphate. The lowest recorded egg total thiamine level was 2.75 nmol/g in 2000. Egg survival to hatch ranged from 20.7% in 2005 to 35.4% in 2002, and was not correlated to egg thiamine levels. Twenty-two spawns experienced total mortality prior to hatch, and had significantly lower egg free thiamine and total thiamine concentrations than eggs from the 77 successful spawns. The eggs from spawns with total mortality were also significantly smaller than those eggs from spawns that did survive, and were produced by females that weighed significantly less. Several small, but significant, correlations were observed between egg size and egg thiamine levels, and female size and liver thiamine.

There was also a significant negative correlation between the number of eggs per spawning female and egg thiamine pyrophosphate, liver thiamine monophosphate, and liver total thiamine levels.

Conclusion:

In general, Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon eggs show little indication of thiamine deficiency in the years sampled, indicating other factors are likely responsible for poor egg survival.

INTRODUCTION

Eggs collected from free-ranging fall Chinook Salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha in Lake Oahe, South Dakota (USA) typically experience poor survival during hatchery rearing [1], with survival less than one-half that observed for Chinook Salmon in their native range [2, 3]. The reason for this elevated egg mortality is currently unknown, but may be due to several factors, including elevated water temperatures during oogenesis and spawning [4, 5], parental nutrition [1, 6, 7], and possible inbreeding [1, 8, 9]. One aspect of parental nutrition that may be influencing reproductive success are thiamine (vitamin B1) levels in the eggs.

In fish, thiamine is found in three different forms or vitamers: thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP), thiamine monophosphate (TMP), and free thiamine. Thiamine pyrophosphate and thiamine monophosphate are the two biologically active forms [10]. TPP and TMP are cofactors required for fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism, specifically the pyruvate decarboxylase complex and enzymes involved in the Krebs cycle [10]. Without these enzymes, aerobic respiration will cease. In addition, thiamine deficiencies are also linked with neurological degenerative disorders such as Weirnkie’s syndrome [10]. Without thiamine, organisms become lethargic and eventually die because of the decrease in metabolism and neuron degeneration.

Rainbow smelt Osmerus mordax are the primary prey item for Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon when they are abundant [11]. Rainbow smelt contain thiaminases, a group of enzymes that break down thiamine [12-14]. Mortality of Salmonid embryos from thiamine deficiencies resulting from the parental consumption of thiaminase-containing prey has been observed in the Baltic Sea, the Finger Lakes of New York, and the Great Lakes [15-19]. Depending on geography, this mortality was initially called M74, Cayuga syndrome, swim-up syndrome, and Early Mortality Syndrome [20]. However, all these syndromes have now been grouped together as the thiamine deficiency complex [21]. During certain years of hatchery rearing, Lake Oahe Salmon exhibits some of the clinical signs, and mortality patterns, associated with thiamine deficiency complex.

Only one preliminary study has described thiamine levels in Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon and eggs [22]. However, this study lasted for only one year, during which rainbow smelt population abundance was low. Smelt and other prey fish populations fluctuate substantially from year-to-year in Lake Oahe, and it is possible that spawning female and egg thiamine levels fluctuate as well. The objective of this study is to document levels of maternal liver and egg thiamine concentrations in conjunction with the reproductive success of Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon over several years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

Lake Oahe is a 150,000 ha mainstem Missouri River reservoir located in North and South Dakota, USA. The South Dakota portion contains approximately 47,755 ha of coldwater habitat (water temperatures ≤ 15° C) at full pool [23]. Suitable permanent habitat for Chinook Salmon is typically located directly upstream from Lake Oahe dam, north of Pierre, South Dakota, to Whitlock’s Bay, west of Gettysburg, South Dakota, USA. Female Salmon and eggs used for this study were collected during spawning of feral Chinook Salmon at Whitlocks Spawning Station on Lake Oahe near Gettysburg, South Dakota. Egg incubation occurred at McNenny State Fish Hatchery, rural Spearfish, South Dakota.

Spawning and Egg Incubation

Eggs were pneumatically removed from ripe, free-ranging females that had ascended the fish ladder at Whitlock’s Spawning Station. Prior to gamete collection, male and female Salmon were anesthetized in carbon-dioxide saturated water. Milt was collected from males by hand-stripping, pooled in a container, and kept on ice until it was used to fertilize the eggs. Eggs were removed from ripe females by injecting compressed oxygen at low pressure into their body cavities and the eggs were expressed into a plastic pan. Lake water (11-13° C, total hardness as CaCO3 = 160 mg/L, pH = 8.2, total dissolved solids = 440 mg/L) was added to the pan to activate the milt. After approximately one minute, eggs were washed in lake water to remove excess milt, and then placed in lake water for one-hour to allow for membrane separation (water hardening). After water hardening, the eggs were placed in plastic bags with fresh lake water, and transported approximately 4 hours to McNenny Hatchery. The spawn from each female was maintained discretely during the spawning process, transportation to the hatchery, and during incubation. Based on historical norms and the size of fish at spawning, it was assumed that only age-3 Salmon were used in the study [24].

Upon arrival at McNenny Hatchery, the eggs were disinfected in a 100 mg/L buffered free-iodine solution for 10 min, inventoried by the water displacement method [25], and placed in individual Heath (Flex-a-lite Consolidated, Tacoma, Washington) incubator trays. Well water (11o C, total hardness as CaCO3 - 360 mg/L, alkalinity as CaCO3 - 210 mg/L, pH - 7.6, total dissolved solids - 390 mg/L) at a flow of 12 L/min was used for egg incubation. Formalin treatments using Parasite-S (37% formaldehyde, 6 to 14% methanol, Western Chemical Inc., Ferndale, Washington) at 1,667 mg/L for 15 min were administered daily until retinal pigments were clearly visible (egg eye-up) at incubation d 30, after which dead eggs were removed and percent survival to eye-up calculated. After egg eye-up, additional dead eggs and dead fry were removed by hand until the fry had nearly completed yolk sac absorption and were moved from the incubator. Survival to the eyed stage of development, hatch, and fry swim-up was calculated using the following formulas:

Survival to the eye (%)

= 100 X [1 - (mortality at the eyed stage / initial number of eggs)].

Survival to hatch (%)

= 100 X [1 - (mortality up to hatch / initial number of eggs)].

Survival to swim-up (%)

= 100 X [1 - (total mortality during incubation / initial number of eggs)].

Thiamine Analysis

Immediately after removal from the female, approximately 20 g of eggs were placed into plastic bags, quickly frozen using dry ice, and subsequently stored in a -70° C freezer until analyzed for thiamine content. Immediately after spawning, the liver was removed from each spawning female, quickly frozen using dry ice, and stored at -70° C until thiamine analysis occurred. Thiamine pyrophosphate, thiamine monophosphate, and free thiamine were analyzed using a high pressure liquid chromatography method [26]. Total thiamine was calculated by adding the vitamers.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using the SPSS (9.0) statistical analysis program (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Regression and correlation analysis were used to ascertain any possible relationships among the variables. Yearly data was analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey means comparison procedure. The significance level for all tests was predetermined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Egg and maternal liver thiamine concentrations varied significantly from year-to-year (Table 1). Free and total thiamine levels in the eggs were the highest in 2001, followed by 2002, with the lowest levels recorded in 2000, 2003 and 2005. Maternal liver TMP and total thiamine were also significantly greater in 2001 compared to the other years. Egg total thiamine levels ranged from 2.75 to 45.25 nmol/g, and maternal liver total thiamine levels ranged from 1.05 to 16.65 nmol/g. Most of the thiamine in the eggs was present as free thiamine, whereas TPP was the predominant form of thiamine found in maternal livers.

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 21 | 21 | 17 | 20 | 20 |

| Length (mm) | 678 ± 13 y | 690 ± 44 y | 776 ± 55 z | 810 ± 6 z | 722 ± 15 y |

| Weight (g) | 2,019 ± 143 x | 2,999 ± 152 y | NA | 4,442 ± 141 z | 3,489 ± 334 y |

| Egg Size (number/ml) | 6.9 ± 0.4 x | 4.6 ± 0.2 z | 5.1 ± 0.3 zy | 4.4 ± 0.1 z | 5.9 ± 0.1 y |

| Number of Eggs | 2,011 ± 160 x | 2,374 ± 161 x | 4,067 ± 259 zy | 4,555 ± 151 z | 3,311 ± 261 y |

| Survival to Eyeup (%) | 36.4 ± 6.5 z | 31.5 ± 8.9 z | 38.1 ± 6.8 z | 29.1 ± 4.7 z | 25.0 ± 5.3 z |

| Survival to Hatch (%) | 27.9 ± 6.7 z | 27.4 ± 3.7 z | 35.4 ± 5.6 z | 25.8 ± 5.0 z | 20.7 ± 4.7 z |

| Survival to Swim-up (%) | 27.7 ± 6.7 z | 27.2 ± 3.7 z | 35.2 ± 5.5 z | 25.3 ± 5.0 z | 17.6 ± 3.8 z |

| Egg TPP1 (nmol/g) | 0.65 ± 0.05 z | 0.40 ± 0.05 zy | 0.40 ± 0.05 zy | 0.30 ± 0.05 y | 0.65 ± 0.05 z |

| Egg TMP2 (nmol/g) | 0.55 ± 0.05 z | 0.50 ± 0.05 z | 0.65 ± 0.05 z | 0.40 ± 0.05 z | 0.45 ± 0.05 z |

| Egg Free Thiamine (nmol/g) | 10.10 ± 1.25 x | 27.95 ± 2.15 z | 21.05 ± 0.90 y | 15.55 ± 1.60 yx | 12.55 ± 1.00 x |

| Egg Total Thiamine (nmol/g) | 11.25 ± 1.25 x | 28.80 ± 2.20 z | 22.10 ± 3.60 y | 16.25 ± 1.65 yx | 13.60 ± 1.05 x |

| Liver TPP1 (nmol/g) | 3.45 ± 0.40 zy | 4.30 ± 0.45 zy | 2.79 ± 0.25 yx | 4.00 ± 0.20 zy | 5.00 ± 3.90 z |

| Liver TMP2 (nmol/g) | 1.95 ± 0.30 y | 3.10 ± 0.40 z | 1.15 ± 0.15 yx | 1.25 ± 0.05 yx | 0.82 ± 0.10 x |

| Liver Free Thiamine (nmol/g) | 0.40 ± 0.05 yx | 1.30 ± 0.20 z | 0.80 ± 0.05 zy | 0.35 ± 0.05 yx | 0.25 ± 0.05 x |

| Liver Total Thiamine (nmol/g) | 5.80 ± 0.60 y | 8.70 ± 0.90 z | 4.75 ± 0.35 y | 4.45 ± 0.55 y | 5.95 ± 0.75 y |

Overall mean survival to the eyed-egg stage was only 31.9%, with mean survival to fry swim-up at 26.4%. No significant differences in egg or fry survival were observed among any of the years. Survival to the eyed-egg stage and fry swim-up of the spawn containing eggs with 2.75 nmol/g total thiamine was 68% and 62%, respectively.

In comparison to eggs from spawns that failed to hatch, eggs from successful spawns with at least some survival to hatch had a significantly greater concentration of free thiamine (13.75 to 18.40 nmol/g) and total thiamine (14.85 to 19.35 nmol/g) (Table 2). Egg TPP and Egg TMP were not significantly different from the two groups. None of the liver thiamine vitamers were significantly different as well. The eggs that did not hatch were significantly smaller (smaller eggs have a higher number of eggs/ml of water displaced) and came from larger females.

| 0% Hatch | > 0% Hatch | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 22 | 77 |

| Length (mm) | 713 ± 15 z | 738 ± 8 z |

| Weight (g) | 2,726 ± 240 y | 3,427 ± 172 z |

| Egg Size (#/ml) | 6.3 ± 0.4 z | 5.1 ± 0.1 y |

| Number of Eggs | 2,886 ± 317 z | 3,217 ± 132 z |

| Survival to Eyeup (%) | 6.6 ± 2.0 y | 39.1 ± 2.4 z |

| Survival to Hatch (%) | 0.0 ± 0.0 y | 35.0 ± 2.3 z |

| Survival to Swim-up (%) | 0.0 ± 0.0 y | 33.9 ± 2.3 z |

| Egg TPP1 (nmol/g) | 0.45 ± 0.05 z | 0.50 ± 0.10 z |

| Egg TMP2 (nmol/g) | 0.65 ± 0.15 z | 0.45 ± 0.05 z |

| Egg Free Thiamine (nmol/g) | 13.75 ± 1.25 y | 18.40 ± 1.10 z |

| Egg Total Thiamine (nmol/g) | 14.85 ± 1.30 y | 19.35 ± 1.10 z |

| Liver TPP1 (nmol/g) | 4.15 ± 0.40 z | 4.00 ± 0.25 z |

| Liver TMP2 (nmol/g) | 1.85 ± 1.15 z | 1.70 ± 0.20 z |

| Liver Free Thiamine (nmol/g) | 0.50 ± 0.10 z | 0.65 ± 0.05 z |

| Liver Total Thiamine (nmol/g) | 5.95 ± 0.60 z | 6.15 ± 0.45 z |

2TMP = thiamine monophosphate.

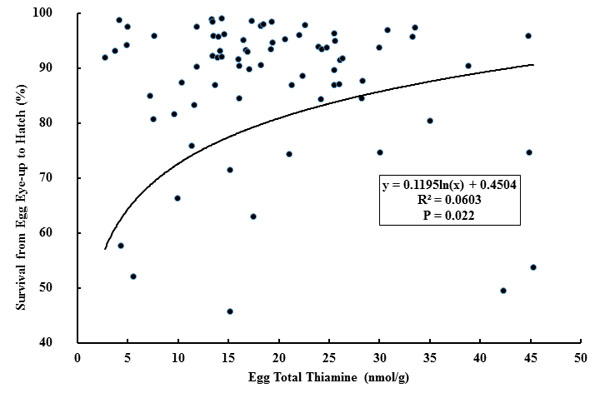

There were no significant correlations observed among survival to the eyed-egg stage, hatch, or fry swim-up and any of the thiamine forms or total thiamine. Egg TPP, TMP, free thiamine, and total thiamine levels were significantly, but weakly, correlated with egg size (Table 3). Small, but significant, correlations were also observed between the number of eggs and liver thiamine levels. Liver free thiamine was significantly correlated with egg free and total thiamine concentrations. There were significant, but weak, correlations between liver total thiamine and spawning female length and weight. Two significant regressions were calculated based on the natural log transformation of egg total thiamine data in relation to the survival from the eyed-egg stage of development to hatch (Fig. 1) and survival from the eyed-egg stage to fry swim-up (Fig. 2).

Female lengths, weights, egg size, and the number of eggs per spawn were significantly different among the years. Fish were the largest in 2002 and 2003. There were significantly fewer eggs per spawn in 2000 and 2001 compared to the other three years and the smallest eggs were observed in 2000, followed by 2005, and then 2001-2003.

|

Fig. (1). Survival from the eyed egg stage to hatch of landlocked Chinook Salmon from Lake Oahe, South Dakota in relation to total egg thiamine from 2000 to 2005 (n = 77). |

DISCUSSION

At 2.75 nmol/g, the lowest concentration of egg total thiamine in the eggs from one spawning female was above the 1.7 noml/g upper boundary for thiamine deficiency complex identified by [27-30]. However, this value (2.75 nmol/g) was slightly less than the 2.99 nmol/g total thiamine value reported to produce 20% mortality in Lake Ontario Chinook Salmon eggs [31], but the overall high survival of the fry, and the lack of substantial post-hatch mortality, from this spawn appears to indicate that mortality due to thiamine deficiency did not occur. Of the 99 spawns sampled in this study, only three showed survival of less than 90% between hatch and swim-up, which is the most lethal period for thiamine deficiency complex [28]. Of these, the lowest concentration of total egg thiamine was 9.25 nmol/g, much greater than the concentration considered the upper end of the thiamine deficiency complex [28, 31], making it unlikely that a lack of thiamine was the cause of fry mortality. The adequacy of thiamine levels in Lake Oahe Salmon observed in this study is further supported by the similar hatch to swim-up survival rates of Lake Oahe Salmon eggs to eggs treated with supplemental thiamine from populations with a history of thiamine deficiency complex [15, 16, 20].

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | P | r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg TPP1 | Egg Size | 0.000 | 0.346 |

| Egg TPP1 | Number of Eggs | 0.033 | -0.215 |

| Egg TMP2 | Egg Size | 0.039 | 0.208 |

| Egg Free Thiamine | Egg Size | 0.003 | -0.293 |

| Egg Free Thiamine | Egg Total Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.998 |

| Egg Free Thiamine | Liver TMP2 | 0.005 | 0.297 |

| Egg Free Thiamine | Liver Free Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.528 |

| Egg Total Thiamine | Liver TMP2 | 0.005 | 0.294 |

| Egg Total Thiamine | Liver Free Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.528 |

| Egg Total Thiamine | Egg Size | 0.008 | -0.267 |

| Liver TPP1 | Liver TMP2 | 0.000 | 0.366 |

| Liver TPP1 | Liver Total Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.816 |

| Liver TMP2 | Length | 0.001 | -0.352 |

| Liver TMP2 | Number of Eggs | 0.000 | -0.416 |

| Liver TMP2 | Liver Free Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.747 |

| Liver TMP2 | Liver Total Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.815 |

| Liver Free Thiamine | Number of Eggs | 0.037 | -0.223 |

| Liver Free Thiamine | Liver Total Thiamine | 0.000 | 0.649 |

| Liver Total Thiamine | Length | 0.002 | -0.326 |

| Liver Total Thiamine | Weight | 0.013 | -0.298 |

| Liver Total Thiamine | Number of Eggs | 0.000 | -0.364 |

| Length | Egg Size | 0.000 | -0.525 |

| Length | Number of Eggs | 0.000 | 0.684 |

| Weight | Egg Size | 0.000 | 0.729 |

| Egg Size | Number of Eggs | 0.000 | -0.372 |

| Egg Size | Survival to Hatch | 0.050 | -0.197 |

| Egg Size | Survival to Swim-up | 0.042 | -0.205 |

| Survival to Hatch | Number of Eggs | 0.050 | 0.198 |

| Survival to Hatch | Survival to Eye-up | 0.000 | 0.963 |

| Survival to Hatch | Survival to Swim-up | 0.000 | 0.994 |

| Survival to Swim-up | Survival to Eye-up | 0.000 | 0.954 |

2TMP = thiamine monophosphate.

The lowest egg total thiamine concentration observed from any spawn during the five years of this study was only slightly lower than the 3.5 nmol/g lowest measurement reported previously for eggs from Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon during a year when smelt were less numerous [22]. Eggs from two of the years had similar total thiamine values to the 9.9 nmol/g mean value in 1999 reported [22]. However, mean values from the other three years were dramatically larger, approaching nearly 29 nmol/g in 2003. The highest recorded egg total thiamine level was also nearly three times that reported by [22].

|

Fig. (2). Survival from egg eye-up to fry swim-up of landlocked Chinook Salmon from Lake Oahe, South Dakota in relation to total egg thiamine from 2000 to 2005 (n = 77). |

Overall, thiamine levels in Chinook Salmon eggs from Lake Oahe are far greater than levels found in the Great Lakes or the Baltic Sea, where thiamine deficiency complex is frequently observed. The minimum total egg thiamine level observed in this study is typical of Chinook Salmon eggs that did not exhibit thiamine deficiency complex from Lakes Michigan and Huron [30]. In Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and Lake Ontario, mean egg total thiamine levels for Salmonids have been reported as 2.0, 3.1, and 1.3 nmol/g, respectively [32]. In the Baltic Sea, egg mean total thiamine levels of 2.7 nmol/g have been reported [33]. The mean values from Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon eggs in the current study are as high as ten times greater as these other locations. However, the lowest levels observed in this study are similar to those reported for suspected thiamine-deficient eggs from migratory Chinook Salmon in New York [34].

Thiamine deficiency complex may not be a problem for the Salmon in Lake Oahe because the concentration of thiaminase in rainbow smelt may not be sufficient for induction of the complex [16]. The amount of thiaminase in rainbow smelt is up to six times less than the amount in alewife Alosa pseudoharengus [16, 35]. Thiaminase activity is also four times lower in smelt than in Baltic herring Clupea harengus [36]. The thiaminase from rainbow smelt may also be diluted by other prey items in the diet of Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon [22], making it likely that there may not be enough thiaminase in the Salmon diet to induce thiamine deficiency complex [37].

The reason for the significantly lower levels of thiamine from spawns where none of the eggs survived to hatch versus successful spawns is unknown. Because of the high prevalence of overripe and nonviable spawns in Lake Oahe Salmon [38], it is possible that thiamine was degraded due to cell death and not because of the action of thiaminase. Twelve of the spawns in the current study had no survival to the eyed-egg stage of development, and were likely nonviable prior to spawning. It is also possible that the thiamine requirements for Oahe Salmon are greater than those in other locations, or there is an interaction between thiamine and other nutritional components, such as fatty acids or bioenergetics [37, 39-42].

Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon are considerably smaller than Chinook Salmon in their native range, likely due to nutritional deficiencies resulting from a total freshwater lifecycle in a reservoir with limited coldwater forage [1]. Lake Oahe Salmon also produce smaller eggs than ocean stocks [1], and the eggs from spawns with no survival in this study were significantly smaller than eggs from spawns with at least some survival. These very small eggs also contained less thiamine, opening the possibility of an interaction between thiamine and other dietary components consumed by the brood female [37, 39-42]. In Lake Oahe Salmon, egg thiamine levels increased with egg size (note that with egg sizes measured as eggs/mL, smaller values represent larger eggs), and egg size increased with maternal length and weight. These larger fish producing larger eggs had a greater ability to acquire more or higher quality food resources [43], which may explain why the eggs from spawns with no survival were smaller and contained less thiamine than eggs that survived.

All of the mean maternal liver total thiamine values were approximately one-third to one-half that reported for Lake Oahe Salmon in 1999 [22]. The Lake Oahe rainbow smelt population also increased after 1999, which may explain this decrease in maternal thiamine. Perhaps of more interest, with the exception of 2001, mean maternal liver total thiamine levels were less than the level of total liver thiamine (6.3 nmol/g) in healthy Atlantic Salmon [18], and very similar to Great Lakes Salmonids producing progeny with Thiamine Deficiency Complex [44]. These relatively low levels may not be lethal, but lower thiamine levels can impact adult fish neurological function [19, 45], metabolic rates [15, 28], and muscle weakness [34], thereby potentially decreasing foraging efficiency and subsequently contributing to smaller body sizes [22, 28].

Similar to that reported by other authors [14, 17, 30, 46], free thiamine was the most prevalent form of thiamine in Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon eggs. Free thiamine likely acts as a storage vitamer and is converted to TPP or TMP later during development [46]. In contrast, TPP was the predominant vitamer in adult tissue. This has also been observed with other adult Salmonids [20, 47], and is not surprising given that TPP is a biologically-active form of thiamine required for cellular metabolism [10].

The relatively weak, but significant, positive correlation between egg size and egg survival observed in this study has been reported for other Salmonids [6, 48]. In contrast, inverse relationships between Chinook Salmon egg size and subsequent survival have been documented, with larger eggs experiencing higher mortality [49]. This was also observed during one year with Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon eggs [1]. However, studies with Chinook Salmon and other Salmonids have found no correlation between the egg size and survival [1, 50, 51].

Even though the Chinook Salmon eggs in this study did not appear to be thiamine deficient, survival was still very poor. Survival to the eyed-egg stage of development has been reported from 83% to 98% from Chinook Salmon in their native range [3, 28, 52, 53]. Egg survival in 2003 and 2005 was also dramatically lower than that previously reported for Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon [1]. Elevated water temperatures during gamete formation and maturation, energy-related maternal dietary issues, and genetic inbreeding may all contribute to the observed poor reproductive success [1, 7, 8, 54].

CONCLUSION

Egg and maternal liver thiamine concentrations in landlocked fall Chinook Salmon from Lake Oahe vary dramatically from year-to-year, likely due to the considerable changes in Salmon prey species abundance and availability that frequently occur in Lake Oahe [1, 55]. The effects on adult fish physiology of relatively low levels of thiamine in maternal livers are unknown, and further research is needed. Lake Oahe Chinook Salmon eggs show no indication of thiamine deficiency, but survival is still relatively poor. Further research is also needed to ascertain the reason for lower thiamine levels in eggs from spawns that experienced total mortality in comparison to successful spawns.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author (editor) declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this study was partially provided by Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration, project F-21-R, study 1587. We thank Jonathan A. Schumacher, Kelly S. Stock, Faraz Farrokhi, Rebecca L. Nutter, Rick Cordes, Will Sayler, Kody Steinbrecher, Fritz Fonck, Dave Stout, Bernie Heath, Brian Smith, John Lott, and Robert P. Hanten for their assistance with egg and tissue collection, thiamine analysis, and egg incubation.